"

"

Two months ago, I woke up in a hostel in Switzerland to a New York Times headline on my phone: “Refugees have been stopped and detained at U.S. airports under President Trump’s immigration ban, prompting legal action.”

I immediately screenshotted it, knowing that it was an image I’d be thankful I saved years from now.

In the days — or even just hours — that followed, countless more headlines lit up my phone, narrating a surreal progression of events taking place back on the other side of the Atlantic. The ban was in place. People were being turned away. People were being sent back. The ban was on hold. Etc.

I cannot imagine what it must be like to experience this tumult back home in the U.S. It’s jarring to hear of these events as an American overseas — but even more so as an American overseas who volunteers with refugees every week.

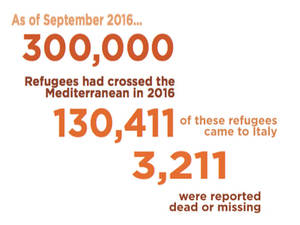

Italy is one of the main countries that refugees from Africa and the Middle East enter when fleeing their homes. Many migrants, waiting to be granted asylum in a process that can take two years or longer — and that can end, after all those years, with rejection — find themselves stuck in Rome, a city struggling to accommodate the influx of newcomers socially, politically and economically. This leaves me half-in, half-out of two intertwined narratives: the ongoing American debate over refugees and the increasingly complex European crisis.

Throughout my travels across Europe, I’ve found that Europeans tend to see American students as wholly representative of the United States, assuming that we agree with everything our government says and does. Considering that, I sometimes wonder if the refugees that I sit and talk to every week think that I see them as terrorists and ‘bad guys.’ If they do, their kindness is hiding it well.

I came to the Joel Nafuma Refugee Center after hearing about a friend’s experiences there last summer. I sometimes wonder what I might think of the center’s patrons if I had been introduced to them through some other avenue, rather than the pre-humanized lens with which I came in. I simply sit and talk with them every week, but even this straightforward task has forced me out of my familiar world and challenged my viewpoints exactly the way a study abroad semester is supposed to. It can be incredibly uncomfortable at times. But as cringe-worthy as some of the language barriers and missed jokes have been, I’ve found that it has made me much more aware of the city around me.

Early one morning, while waiting to catch a train, I noticed a man sitting alone in the very back corner of the station coffee shop, clearly trying to make himself as invisible as possible. He was a bit dirty and worse for wear, carrying what looked like all of his possessions in a torn-up duffel bag — the sort of man your mom would tell you to sit far away from. And, duly, everyone had taken the tables on the other side of the shop from him, leaving him isolated. He was huddled over some activity in his lap that had wholly engaged his attention. Fresh-to-Rome Me would have written him off as seedy and taken a seat on the other side of the room.

When I passed by him, however, I saw that he was hunched over a notebook in his lap, copying, over and over in painfully meticulous handwriting, an English alphabet.

My experience of walking around Rome has completely changed. I’ve realized now that many of the vendors who hassle you on the street, trying to force cheap bracelets on your wrist to compel you to buy them, or the homeless men that reach out a cup to beg from you on the bridge or even the pickpocketers that get a little too close to you on the bus, aren’t just invasive or annoying or trying to make you uncomfortable. Many of them are refugees, forced into their current states by circumstances beyond their control. I cannot imagine how degrading it must feel to have to beg in public or sell flimsy bracelets beside a bridge to sustain oneself and one’s family.

These encounters, however brief, have made me feel a lot more in Rome than any picture in front of Ponte Sisto ever could. While studying abroad, I’ve often found it frustrating how limited my ability to truly immerse myself in another country has been — especially when ‘experiencing new cultures’ often equates to a few days in a popular city, at a touristy restaurant, the perfect Instagram shot at the most photographed attraction and then a quick flight back to my American university in Rome. But volunteering with refugees has made me feel more ingrained than ever in the city I’m in — and the world in which I live.