"

"

Author's Note: My summer job, like that of many other college students, is at a restaurant. Sometimes, our weekend shifts don’t end until the early hours of the morning. I am lucky to live close enough to the restaurant that I can walk to and from work, but many others don’t have that luxury. My hometown of Ann Arbor, Michigan, is about the same size as South Bend. In other words, it is large enough for a bus system but not for the kind of round-the-clock transport that is found in many major cities. A few of my coworkers had to rely on family, friends and sometimes even rideshare apps once the buses stopped running — and the latter can quickly get expensive. I was interested to see if this was also an issue in South Bend and if it impacted more than just the individuals themselves. While there are no simple solutions, it is clear that a lack of adequate public transportation has negative consequences for our local community.

“A sense of dread”

Lack of robust transit system hurts workers and businesses

Lisa McDaniel was finishing up her shift as a cook at Frank’s Place, a bar and restaurant in downtown South Bend, when she felt a familiar sense of trepidation building as the clock crept towards 2 a.m.

Once she left the relative comfort of the restaurant’s kitchen, she would have to walk back to her home in Mishawaka — through the pouring rain or the bitter winter cold. Perhaps, if she were lucky, the night would be clear and the only thing she’d have to worry about would be avoiding a potential robbery.

“Knowing that you had to walk — it was just a sense of dread,” McDaniel said. “During the day it’s not too bad, but at night, if it’s raining or it’s foggy or anything, it doesn’t matter, you have to be out in the elements.”

At the time, she had no money to buy a car, there was no one to give her a ride so late at night and the buses had stopped running hours earlier.

Even on her days off, McDaniel felt the impact of the lack of reliable transportation. She put off medical appointments because it was too difficult to find a ride. In addition to paying attention to costs at the grocery store, she also had to ensure her bags were not too heavy, lest they break on her walk home.

McDaniel’s story is not unique in a mid-sized, automobile-dependent city like South Bend. Although the vast majority of individuals in South Bend own cars, more than 2,000 households do not own a personal vehicle, according to data from the 2018 American Community Survey.

The South Bend Public Transportation Corporation — or Transpo, as it is more commonly known — only runs until about 10 p.m. on weekdays, 7 p.m. on Saturdays and does not run at all on Sundays. Many routes are even more limited.

These limited hours leave many Michiana residents without a car facing a serious challenge getting to work, which hurts them, as well as employers who need workers with reliable transportation.

According to Amy Hill, Transpo’s general manager and CEO, Transpo’s schedule is typical for a system of its size, but she acknowledged the issues that the gaps in service can pose for many.

“We know that presents a challenge for a lot of individuals that rely on public transportation to get to work, especially [in the] service industry where they're working first, second, third shifts [or] working weekends,” she said. “We know that there's a need out there for additional service, especially on Saturdays and on Sundays. For us, it comes down to funding.”

Others have approached the problem from a different perspective beyond the traditional fixed-route bus system. In 2018, the city was the recipient of the three-year, $1 million grant from the Bloomberg Philanthropies U.S. Mayors Challenge, a competitive award given to cities to test innovative programs designed to address pressing social problems. South Bend created Commuter’s Trust, a program which, among other things, subsidizes Uber and Lyft rides for employees traveling to and from work.

However, despite these efforts, transportation remains a problem for many individuals and presents one of the largest barriers to employment. A 2016 study found that the lack of reliable transportation is estimated to be a primary barrier to employment for about 10,000 individuals in St. Joseph County.

The costs associated with the lack of round-the-clock public transportation aren’t solely borne by workers either. Commuter’s Trust estimated that transportation-related turnover likely costs employers across the region more than $3 million annually. Many businesses are struggling to find employees as the economy picks back up, and transportation is a key barrier.

Amish Shah, CEO of Kem Krest, an Elkhart-based manufacturing firm, says that finding labor is among the biggest challenges currently facing his business. As of May 3, Kem Krest had more than 90 openings it was looking to fill.

“Every single business in the Elkhart county area is going to have a ‘Help Wanted’ sign,” Shah said.

He noted transportation as one of the biggest reasons for this difficulty, as the majority of his employees live within roughly five miles of their job locations due to the lack of public transportation infrastructure.

“I'm fishing from the same pond that everybody in the industrial zone is fishing from, and that little pond becomes smaller the more lines that you put in the water,” Shah said. “Today, everybody's sitting there in this pond with a ton of lines in the water.”

Finding labor is such a significant issue for Kem Krest that the company is considering providing its own transportation. Shah noted that there are pockets within the region that have higher unemployment, and Kem Krest is considering chartering a bus to bring employees in from those areas. Shah estimates that this would cost the company about $100,000.

Even once Kem Krest finds employees, transportation is still a significant issue for the firm. Some employees share a vehicle with family members, others carpool and some walk or ride their bikes to work, which can prove challenging in the winter months.

Shah estimated that about 30% of Kem Krest’s employees lack reliable transportation to get to and from work, which leads to late arrivals, absenteeism and higher turnover. Turnover costs Kem Krest about $6,000 per head, and Shah estimated that between 10 and 15 percent of the company's turnover is due to transportation-related issues.

Unreliable transportation can also have other less measurable impacts, such as lower productivity and job satisfaction.

“We as human beings like to have control, at least control over the things that matter in our lives. You want to be able to control how you get to and from work,” Shah said. “I think once you lose control or it becomes a challenge, you almost start to lose a little bit of hope.”

As Hill noted, a primary reason Transpo cannot provide additional service is its financial limitations. According to the Indiana Department of Transportation (INDOT) 2019 annual report, Transpo’s revenue from fares and contracts was less than $2.5 million. The remainder of its approximately $11 million budget came from local, state and federal funding.

“Right now, we’re just trying to keep the same amount, because we’re actually seeing a decrease in funding,” Hill said.

Another problem Transpo has had to grapple with is a steadily decreasing number of riders. According to the INDOT report, Transpo saw nearly an 18 percent decline between 2015 and 2019. The 2020 report is not yet available, but Transpo saw a “significant decline in ridership” due to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a press release in April of last year.

Hill attributed these changes in riderships to fluctuations in the economy.

“When unemployment is very low and people are getting jobs, they’re getting better employment opportunities. They may be able to purchase a personal auto and then typically the ridership goes down,” she said. “When unemployment is very high, our ridership will go up.”

About 80-85% of Transpo’s riders are transit-dependent, meaning they have no other option for transportation, according to Hill. Transpo has long struggled to attract what she called the “choice rider,” someone who owns a personal vehicle or has the means to purchase one yet elects to take public transit.

“If it’s going to take you an hour to go somewhere on the bus when it takes you five or 10 minutes to drive your car, you’re not going to do it,” she said.

Aside from the lack of funding, Transpo faces other hurdles to expanding service, including paratransit services. Paratransit provides flexible transportation options to accommodate people who cannot utilize the existing standard fixed-route system. Transpo’s fixed route fare is $1, but according to Hill, it costs between $4 and $5 to provide.

If Transpo were to expand services, they would be legally obligated to expand paratransit service as well, which costs upwards of $20 per ride to provide, yet the government only permits agencies to charge double the fixed-route fare of $1.

A few years ago, Transpo considered a pilot program to provide transportation on Sunday, but found it to be cost-prohibitive.

“Even if you could get pilot program funding, you don’t necessarily want to provide that service and then take it away when the money runs out,” Hill said. “The last thing you want to do is introduce this pilot program that everybody loves, and then (say) ‘Oh, sorry, we’re out of money’ when you take it away.”

Later this year, Hill said Transpo hopes to begin its first comprehensive operational analysis in 10 years. The company will work with the Michiana Area Council of Governors in order to evaluate its current schedule and routes, as well as potential adjustments.

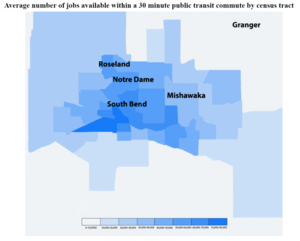

Larger systems are often able to change routes based on demand on a regular basis, but Transpo, which doesn’t have a transit planner on staff, is relatively static. According to data from the American Community Survey and the Center for Neighborhood Technology, Transpo has been highly effective at connecting the poorest neighborhoods within South Bend to employment opportunities.

The poorest census tracts — primarily located on the west side of the city — are among the best connected to jobs via public transportation. However, according to a 2013 study by the Urban Institute, low-income and non-white workers are disproportionately likely to work nights and weekends, when public transportation is not available. Additionally, the number of jobs accessible via transportation is much lower for those who live outside the city limits.

Daniel Graff, a professor at Notre Dame and director of the Higgins Labor Program, said that transportation is important in what constitutes a just wage.

“A just wage should accommodate ease of getting to and from work,” he said. “It shouldn’t be another burden, especially for [a] low wage laborer.”

Graff pointed to the cultural dependence on cars as a primary reason why the United States lacks public transportation infrastructure when compared with other developed countries.

“The U.S. is such a car-based culture, and that’s the problem,” he said. “The public, through government, has created and facilitated and allowed that system, which… furthers all sorts of inequities.”

According to Graff, the lack of a robust public transportation system can contribute to poverty traps, persistent inequality and social justice issues.

“A mass transit system can be a great social good that can foster solidarity and bring people together,” he said. “A weak one or a non-existent one, it just ends up exacerbating the social inequalities.”

Taking advantage of new technologies is key to the future of public transportation, especially when it comes to providing service to areas with lower demand, according to Commuter’s Trust Director Aaron Steiner.

“There’s some fascinating things happening where, because of technology, there’s more ability for things to be on demand,” Steiner said. “Instead of having a fixed route schedule for a bus, you just have a zone that a bus covers or a vehicle, and then they just come and go where people need it.”

This is especially pertinent to a city like South Bend which is not very densely populated. “It’s just really difficult with the demand that there is for a public transit agency to be able to meet the needs of the community,” Steiner said.

Commuter’s Trust has worked to leverage this existing technology by subsidizing rideshare services for its participants. Participants typically pay between $3 and $5 per ride, depending on their employer, who helps pay for the program. The program works with a variety of area employers, such as Notre Dame, Oaklawn Psychiatric Center and the South Bend Community School Corporation.

However, a reliance on technology can leave out the most vulnerable populations.

“Some of the innovation in transportation and mobility is all reliant on access to technology and being connected, but that's going to only continue to leave out these populations that have been underserved and face transportation insecurity,” Steiner said.

Additionally, depending on their employer, participants are limited to a certain number of rides per month. In the case of the school district, that limit is 10. “It’s definitely not going to cover everyday trips back and forth, but it’s enough to meet the needs here and there,” Steiner said.

In its Phase 2 report, the program concluded that it is a good solution for those facing “temporary or moderate transportation insecurity, and less so for those facing chronic or severe insecurity.”

Despite these challenges, Commuter’s Trust has seen a great deal of success in the past two years. It has served nearly 200 participants and provided nearly 4,500 rideshare rides according to the data portal on its website. The Trust also provides Transpo passes for their participants to help them utilize the existing infrastructure.

Commuter’s Trust hopes to continue to expand, even once the grant from the Mayors Challenge runs out, including into the manufacturing hubs in and around Elkhart.

There is no straightforward solution to the problem of public transportation, especially in South Bend, which faces its own unique set of challenges. However, it is clear that in the current system, many are left with few options.

While she is no public transportation expert, McDaniel is uniquely positioned to understand the needs of the community. After about six months of trekking back and forth from Frank’s Place, she was eventually able to secure a small loan and purchase a used car.

The car allowed her to get a better job and some time for much-needed relaxation. Others, however, aren’t so lucky, and are left walking home late night after night with no bus in sight.

“They should have at least one until midnight, until most people are off their jobs,” she said. “Especially people that work in the food industry — sometimes they don’t get off until 9 or 10 o’clock. You can call a cab or an Uber, but you’re going to spend [a lot of money]. They need to expand the bus system. There’s a lot of places it doesn’t go.”