"

"

Numerous students and professors in the Mendoza College of Business say they disagree with the required grade distributions for undergraduate business courses, but the Mendoza administration stresses that the policy does not disadvantage students and plays an integral role in the success of the College.

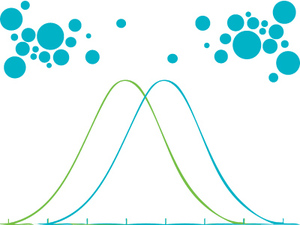

Mendoza’s Departmental Grading Guidelines, which were implemented in the Spring 2010 semester, set an average GPA range that all sections of business courses must fall within. The guidelines vary slightly by classification (ACCT, MGT, FIN, etc.) and level (sophomore, junior or senior) within the College’s base guideline of 3.0 to 3.4.

The Guidelines were employed as a way to standardize grading throughout Mendoza in response to inconsistent departmental grade policies.

“The policy established greater consistency across the college and ensured grading reflected historical averages,” Dale Nees, Mendoza Assistant Dean for Undergraduate Studies, says. “We feel our grades should have that historical perspective. This is where grade averages have been ... Mendoza’s average section grades have remained consistent since implementing this policy.”

However, a number of professors and students question the guidelines’ effectiveness, contending that it does more harm than good for business students.

Chris Stevens, an adjunct professor in Mendoza, has taught Principles of Management, Business Problem Solving and Sales Management for Entrepreneurs to approximately 800 undergraduate students over the past three years. He says the guidelines force professors to give lower grades than students deserve.

“I have to curve certain grades down, and that does not feel right at all. I think it’s dead wrong,” Stevens says. “I think the students should receive the grade that they earn.”

“This unnecessarily forces a comparison versus other students, and academics should be about what a student learns, not who they’re better than, [or] who they’re worse than,” he says.

Stevens emphasizes that the guidelines are especially tough to apply given the level of academic performance he observes from Mendoza students. He recalls a recent example in one of his undergraduate courses that exemplifies the quality of work he sees from business students.

“We just did presentations to the Stryker Corporation. With one week’s notice, my entire class had to learn about a $9 billion health care company. We did 21 presentations to them in less than a week, and Stryker was blown away,” Stevens says. “If students are able to do that, then they should receive the excellent grade that even the customer is telling us that they should get.”

Ezra Kim, a junior Marketing major in Mendoza, echoes Stevens’ sentiment about the forced grade distribution.

“I don’t think it’s fair to the students to have it curved down when they put so much effort into their work,” Kim says. “It’s not really grade inflation if people actually put in the work and they work hard for their grades.”

Kim believes the guidelines could negatively impact Mendoza students in the job market as well.

“When employers look at Notre Dame and another academically comparable institution that doesn’t have a curve — and they don’t know about Notre Dame’s curve — they’re going to assume that the students at the other institution are just more capable based on GPA,” Kim says.

Nees, on the other hand, says the College’s grade distribution does not disadvantage students in employment searches or in the classroom.

“When you get back to the big scheme of things, our students are getting hired,” Nees says. “We have no problems there. People need to recognize that the tenth of a point or whatever, it may be isn’t that critical — it’s more of what else you have going in your favor.”

In addition, Bloomberg has ranked Mendoza the best undergraduate business school in the United States for five straight years.

Nees also rejects the notion that the guidelines promote a heightened sense of competition among business students, citing the collaborative structure of many Mendoza courses.

“We, more than most schools, do group work,” Nees says. “When it comes to when you’re allowed to do group studies or group work, you collaborate just fine, you work together. At the same time, if someone wants to put in the effort, they should be rewarded. That’s how it works in the real world.”

This kind of differentiation exists between students in Mendoza, Nees says. The guidelines thus ensure that professors develop challenging curriculum that evaluates students based on their performance differences.

“It holds our instructors accountable, and I think that’s important,” he says. “Especially at an institution like Notre Dame, if you are not challenging folks — if [students] are not learning something new — then are they really learning? I think this is just another thing that helps that output.”

By encouraging professors to challenge students and differentiate grades, Nees says the guidelines allow Mendoza to better assess its performance as a college.

“This is our attempt to say ‘Let’s make sure that we’re truly and fairly evaluating where we are so we know if we need to be improving.’”

It seems clear that the College will not be changing its grading policy any time soon.