"

"

Outside Notre Dame Stadium, a bronze sculpture of Knute Rockne rests atop an inscription: “105 WINS, 12 LOSSES, 5 TIES.” A legendary head football coach, Rockne led Notre Dame to tremendous football victories. But according to Notre Dame professor of American Studies Annie Coleman, he also understood the power of theater, marketing and spectacle.

Beginning in the 19th century, Coleman said American colleges across the country began building up their football teams to promote their school brand and recruit a more diverse student body. Now, college football has become a multibillion-dollar industry. Notre Dame currently generates over $100 million per year from its football team, according to the Wall Street Journal. However, player advocates say all that profit and spectacle has come at a cost. Two former Notre Dame football players have filed lawsuits against Notre Dame and the NCAA after they developed a neurodegenerative brain disease that they say came from their time on the field.

In the mid-1990s, the medical community began finding that football players, after repeated concussions, developed a degenerative brain disease called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. A 2017 Boston University study examined the brains of 53 former college football players, and found that 91% of them had CTE. According to Boston University’s CTE Center, the disease leads to memory loss, cognitive decay and mood problems — it can be lethal and has no known cure.

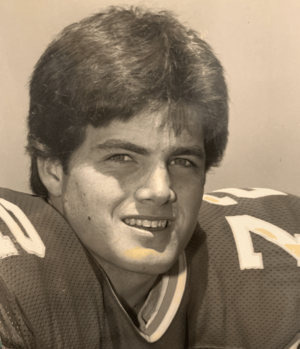

Steve Schmitz, was a running back and receiver for the Fighting Irish from 1974-78. All those tackles and collisions would eventually lead him to develop memory loss and personality change, according to a complaint filed in the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas.

Schmitz alleged in the complaint that Notre Dame coaches encouraged him and his teammates to lead into plays with their helmets and never warned him that he was at risk for CTE. Courts papers show that Schmitz, who was never tested for concussion symptoms, didn’t realize he had even sustained a concussion while on the team.

Schmitz’s football career ended when he graduated from Notre Dame, but his football injuries followed him, and he ultimately became unemployed, the complaint said. In 2012, a neurologist diagnosed him with CTE. He died in February 2015.

John Askin was an offensive lineman for Notre Dame from 1982-86. In a complaint filed in Jefferson Circuit Court, Askin — like Schmitz — was told to lead into plays with his helmet. According to Askin’s complaint, the university never warned him of the risk of CTE.

In his complaint, Askin alleged that during his time on the team, Notre Dame coaches illegally supplied players unprescribed pain medications. His attorney J. Bruce Miller argued that the pain medication desensitized Askin and his teammates to concussive symptoms. Miller told Scholastic that coaches distributed the pain medication that also was a blood-thinning agent at halftime or on plane rides back from games. When players hit their heads with the pain medication in their bloodstream, Miller said, they were susceptible to brain bleeds.

After retiring from football, Askin had clear physical injuries from his football days — injuries that ultimately forced him to retire early and live on disability checks. But Askin’s neurological symptoms were not apparent until later, said Miller. In February 2018 a neurologist officially diagnosed Askin with a neurodegenerative illness that is most likely CTE.

“The Askin case is pending in Kentucky state court, and the Schmitz case is pending in Ohio state court,” Dennis Brown, a university spokesman, told Scholastic. “Both cases are in the early stages of litigation. In each, we are confident in our position as set forth in our court filings.”

In both Schmitz and Askin’s cases, Notre Dame attorneys said the players should’ve recognized their injuries sooner, and they argued the statute of limitations has run out. Schmitz and Askin both argued they filed their claims within a reasonable time frame after they discovered their conditions. The courts will ultimately decide.

Brown added, “The health and safety of our student-athletes has always been a priority for Notre Dame, and over the years we have provided them with the best equipment, protocols and care available at the time.”

However, the Askin complaint said the university and NCAA withheld information from him, developed no protocol to communicate and mitigate those risks and were “willfully blind” to the risks he and other players faced. Notre Dame ignored these risks, the complaint said, “for one purpose: to entertain the audience for Notre Dame football and to reap profits from Notre Dame football games and broadcast contracts.”

As more details emerge about the dangers of CTE, Coleman said she expects that cultural perceptions of football will shift.

“It’s easy for us to hold those two things in our heads at the same time as human beings — to appreciate the game and the excellence it represents and also have to deal with the physical consequences,” she said. “It’ll be interesting to see how the game changes.”