"

"

A gust of arctic wind brushes a metallic, shining cheek as snowflakes cascade quickly into an outstretched hand. During every moment of every day, holding a wakeful repose even in the darkest nighttime, the golden figure of Mary sits atop her dome of the same ilk. And down beneath the wooden beams and frescoes and plaster, within the building some might call her “house,” the modern leaders of Notre Dame have a home.

Here, in 400 Main Building, the university president and his staff work tirelessly each day to ensure that their human leadership makes just as solid an impression on the community and the larger world as the golden statue of Mary has for over a century. For the university president, each day on the job presents different challenges and joys. While routine tasks such as making phone calls, sending emails, writing speeches and drafting announcements will never drop from the docket, more spontaneous events, from adventures around the world to crises, come along to complicate “a typical day.”

Aspects of the university president’s experience will always remain the same, while evolving social and political contexts here on campus and around the world have shaped the responsibilities of Notre Dame’s largest leader in remarkable ways. At this point in time, the Notre Dame community has the opportunity to understand the lives of its presidents over a long swath of time and history — the university’s two living presidents emeritus, Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. and Rev. Edward “Monk” Malloy, C.S.C. and its current president Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., have held tenures spanning the past 62 years.

Notre Dame has been profoundly shaped by each “day in the life” experienced by these men. And, as conversations with each of them reveal, navigating the presidency has transformed their lives just as much. From Father Hesburgh’s calm pride in recalling his commitment to co-education, to Father Malloy’s dedication to his vocation as a teacher and Father Jenkins’ decision to welcome President Barack Obama to campus amidst much vitriol — every presidential day holds historic meaning and adds its stories to a ledger from which we can all learn multitudes.

Father Ted Hesburgh (President 1952-1987)

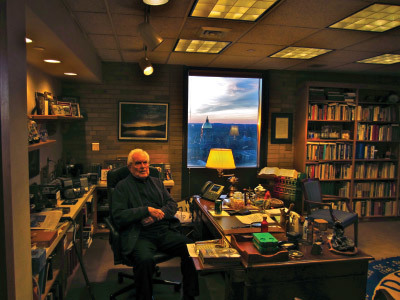

A faint orange glow alights from a small circle of plastic: The number 13 marks the spot, and within a few seconds, an elevator has begun to zip up and up and up, to the very top of the Hesburgh Library. It is fitting that Notre Dame’s most esteemed president enjoys office space in a building bearing his name, but the man himself gives off practically no air of self-importance.

“I’m not impressed anymore by medals or honors because what happened, happened, and sometimes you can’t plan it, you came along just at the right time,” Father Hesburgh says of his successes.

And while Hesburgh does take care to display his most prestigious awards — namely the Presidential Medal of Freedom (the highest civilian honor in the United States) and a ring given to him by the Pope — just outside his main office room, he does not let these displays dominate the space. Hundreds of curios populate Hesburgh’s expansive shelves and cabinets, including wooden sculptures acquired during travels to Latin America and framed photographs of the president emeritus flying at more than the speed of sound in a Blackbird fighter jet and holding by the mouth “the biggest fish ever caught” in Land O’ Lakes, Wisc.

These days, Hesburgh spends most of his time here, speaking with students about their various concerns and curiosities, reading newspapers and magazines with some assistance from students happy to help and generally leading a “relaxed” life.

“I have a good life, and I thank God for that. I’ve had Mass every single day ever since I’ve been ordained. And if I say thank you to God, I say thank you for making me a human being in this world,” Hesburgh says.

Not all of his days at Notre Dame have been this peaceful, though. When looking back upon the biggest accomplishments and most memorable moments of his presidency, Hesburgh speaks about his decision to welcome female students to Notre Dame in 1972 and of the tumult that arose as a result.

“I felt early on that we were only doing half the job, as we were turning out a thousand or two men every year, but the world isn’t run by men,” Hesburgh says. “So I told the trustees that we were going to open [Notre Dame] to women, and they said, ‘You’ll ruin the place.’ … And I said, “I’m not going to ruin it. I’m going to make it better.’”

Hesburgh says that, before the introduction of co-education, Notre Dame was limiting its impact on the national and global communities. Disregarding the traditional “macho” mentality of the university at the time, he sought to draw the most thoughtful students to Notre Dame, no matter their sex, in order to make as large a dent as possible in wrestling with issues of importance. “That’s a monumental change, taking half of the human race that wasn’t able to come here before, and now letting them not only come, but excel,” he says.

In addition to breaking new ground on historic transitions such as the move to co-education, Hesburgh was tasked with managing the same, more routine responsibilities as all of his predecessors and successors: meeting with people and responding to misconduct.

“Meetings are a pain in the neck half the time, and the other half they’re delightful,” Hesburgh says. He recognizes that struggling through meetings with disagreeable people is inevitable in the duties of “the head guy,” adding that such occurrences happened rarely.

In a similar vein, Hesburgh recalls having to leverage punishment following incidents of employee or student misconduct, even though he characterizes such incidents as few and far between. “As a top guy, you have to deal with that because that kind of person is corrosive within the organization,” Hesburgh says. “Luckily, because we have such a tough admissions process, we don’t have to deal with that problem very often.”

Partially due to Notre Dame’s high admission standards for students, Hesburgh says that students have retained consistent characteristics since he first took over as president. He says that while students today are “a little more sophisticated and a little smarter and they’ve had better [pre-college] educations,” the fact remains that “students are students.”

Hesburgh specifically emphasizes Notre Dame students’ unchanging potential to build upon their classroom experiences in impacting the world. He tells a story of the first class he taught at Notre Dame and of a student who maintained a constant stream of chatter, disrupting Hesburgh’s concentration and heightening his new-teacher nerves. The student, it turns out, did not speak English fluently and was attempting to keep up by asking his peers for help translating the lecture. This man, with whom Hesburgh built a meaningful relationship, was named Napoleon Duarte, and he would one day become the president of El Salvador.

Hesburgh says that, as Duarte’s example shows, Notre Dame provides its students with opportunities to learn important lessons that they can leave with and return to throughout their years as life-long leaders. “I think [Notre Dame] is just a great place to grow up because growing up is facing the problems that you’re going to face for the rest of your life and maturing from that,” he says.

And, as far as any advice he has to offer current students, Hesburgh recommends attending Mass more often and making good use of the resources offered by the scores of Holy Cross priests and brothers who live on campus, including himself.

“The door is always open. Anybody, including the latest freshman to arrive to a graduating senior or graduate student, is welcome,” Hesburgh says.

Looking forward into the future, Hesburgh says that Notre Dame, as the “top Catholic university in the world,” has the potential to foster excellence throughout the institution.

“The universities with the top endowments are the best because they can afford to have the best faculty and to offer scholarships to the best students, and I worked very hard on that during my time,” he says. “I think today we’re very close to the top, including the best students and best faculty in the country. That’s what I’m most happy about.”

Father Edward "Monk" Malloy (President 1987-2005)

Upon first meeting the 6-foot-4 Father Edward “Monk” Malloy, the story of his initial arrival at Notre Dame makes complete sense: “I was recruited to play basketball at Notre Dame. I had about 55 offers from different schools,” Malloy says, but “when I came [to Notre Dame] I just knew it was the place for me.”

Malloy received his B.A. and M.A. in English and an M.A. in theology from Notre Dame in 1963, 1967 and 1969, respectively. After his ordination as a Holy Cross priest in 1970 — and after earning a Ph.D. in Christian Ethics from Vanderbilt along the way — Malloy began to teach at Notre Dame, and he continues to do so today. He works out of an office on the third floor of DeBartolo Hall, and his view overlooks the quad and the Mendoza College of Business.

Malloy has also maintained a direct connection to the students through his choice to live in Sorin College for the past 34 years. Malloy finds that he can better live out his vocation by teaching and living in a community with the students. “I think that the genius of Holy Cross is that our charism, our gift as a religious community, is to be well-trained and to do many things as well as you can simultaneously,” he says.

Malloy says that his choice to teach and live in a dorm throughout his presidency and now represents “a natural outflow from what I had been doing and what I enjoyed doing. I didn’t want the presidency to take me away from that,” he says.

When he became university president in 1987, Malloy remained committed to these parts of his life, but he also recalls now the ways his life changed rather quickly. “I remember walking back from the Trustee meeting and thinking, ‘My life on campus is not going to be the same,’” Malloy says. “Students related to me in a different way, faculty related to me in a different way, and so on. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

Malloy received the torch from Father Hesburgh, who had held the position of president for 35 years and had garnered a degree of international fame. “Father Hesburgh was certainly a legend and one of the great figures of higher education and of American life,” Malloy says of his predecessor. He credits Hesburgh with leaving the university in a positive place, so that Malloy and the administration could build upon prior successes.

Malloy recalls that no two days as president were alike. He says that some days were focused solely on one activity, like a home football Saturday, and that most of his work revolved around representing the university to various constituencies. Arriving in his office at around 9:00 a.m. each morning, Malloy attempted to leave enough gaps in his schedule so that members of the administration, faculty, staff and visitors could have access to him.

Malloy says that, during his 18 years in office, he tried to meet with all of the professors who had been promoted to tenured positions, as well annually sitting down with the Academic Council, faculty senate, new leaders in student government and the new staff of The Observer.

While Malloy remembers this stream of interaction as “fun” and in keeping with his outgoing personality, he also characterizes “people, people, people” as the largest challenge of the presidency. Specifically, he says that “hiring people, holding them accountable [and] sometimes firing them” represented major tasks of his job. Beyond all of that responsibility, Malloy says striving to create a positive work environment was part of the challenge.

“Trying to bring out the best in the people you work with — trying to inspire them and encourage them and thank them … Those are all tasks of leadership,” he says.

One occasion that challenged Malloy to serve and support the people of Notre Dame during a time of great uncertainty came on Sept. 11, 2001. Looking back, Malloy calls the sunny Tuesday the most significant day of his presidency.

“That morning so many things changed and we had to determine what we were going to do. Everything was up for grabs,” he says. “We thought, for example, that a lot of parents of Notre Dame students might have been killed. And we didn’t know when it was going to end.”

Malloy recalls walking around the lakes after he had witnessed that morning’s tragedies, trying to decide what message to share with the community at the South Quad Mass planned for later that evening. In the end, he decided to focus his homily on the image of the Scared Heart of Jesus Christ statue. “This image of an open armed, compassionate Christ is what I said is consoling us in our time of sorrow,” Malloy says.

After the Mass ended, Malloy remembers that there was utter quiet and some hesitancy to vacate the space. “No one wanted to leave. It was very consoling to be together,” he says. “I will never forget that. It was a tragic moment, but a really positive one as far as an experience in the Notre Dame community.”

And when asked about how the students in the Notre Dame community have changed during his time at the university, Malloy says that he has noticed a general improvement in early academic capability over the years. “As a teacher I would say the biggest change is that the bottom third isn’t there anymore, academically. It’s really hard to grade, because in my experience, at least the students I teach are all very capable and very smart,” he says.

And while Malloy says that some changes in the student body are merely a reflection of changing times — such as students’ propensity to “plug in” and their more frequent experiences traveling early in life — he says that the biggest change in the student body is its increasing diversity. “It’s more evenly male and female; it’s more international. It’s more of the things that were part of the goals that we set,” he says.

Malloy says that this increased diversity means that Notre Dame’s students have had a wider array of experiences with the Church than could be said of previous generations. He says that “the manifest religiosity of the student body” has declined during the past 30 years. Malloy appreciates the modern rituals of “milkshake Masses” and “chili Masses” that bring people together in the dorms, and he realizes that changes to Notre Dame’s religious life, such as these, arise naturally. “It would be naïve not to know that people relate to [the Church] in a different way than they used to. It’s part of the challenges and the opportunities that we have,” Malloy says.

Despite challenges he faced as university president, Malloy looks back upon his time in office with pride for certain accomplishments. When asked specifically what those were, he immediately recites a litany of feats, including preserving and enhancing the quality of undergraduate education, building higher quality graduate degree programs, becoming more international in all aspects of the institution, fundraising and budgeting effectively and furthering the university’s Catholic mission.

Malloy also counts a boom in physical construction as an accomplishment made during his time as president. He points to the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center, all of the West Quad dorms and the expansion of Notre Dame Stadium as notable and successful projects.

Malloy does take care to pause and give credit to his colleagues with whom he worked closely to make all of this progress a reality. “I thought I had in my administration a lot of people who had the talent, if they want to be president someday,” he says. “I don’t want to attribute all this to me; it was all these good people who worked cooperatively.”

Looking forward, Malloy says that Notre Dame’s current administration, faculty members and students have the potential to work together to become “the first great Catholic, fully-fledged research university in American history.” Comparing Notre Dame to peer institutions Boston College and Georgetown University, Malloy says that Notre Dame has a chance to make unique strides in the coming years. “Right now, I think we’re best situated to [invest in research], and for us to pull back in the face of that challenge would be inappropriate,” he says.

And while Malloy leans back in his chair and gestures toward the stadium in his approximation of great things to come in the realm of stimulating research, he does say that Notre Dame should continue to emphasize quality undergraduate instruction along with its outside interests. “I think that’s our particular call at this moment in history and, God willing, we will be successful,” Malloy says.

When he’s not pausing to ponder the future of the university he has called home for so many decades, Malloy continues to enjoy teaching a seminar for freshmen on the genre of autobiography. He also spends time unwinding, albeit in remarkably productive ways.

“I write book and movie reviews,” Malloy says. “I watch more movies than even the students do. I have a diary that comes out every semester and in the summer, and I just reviewed 100 movies and 50 books.”

Malloy claims the title of “master crossword puzzle doer,” as he says — perhaps facetiously, but with a mysterious air of certainty — that he has completed every puzzle in the history of The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The San Francisco Examiner, The Wall Street Journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Chicago Tribune.

“I do [crosswords] for fun, for relaxation and enjoyment,” Malloy says.

Malloy also says that while he does not watch much live TV beyond sports and the news, he does follow a few series, such as “Downton Abbey,” “Homeland” and “Breaking Bad.”

A love for traveling rounds out Malloy’s self-described gamut of interests, and, when asked to name a few of his favorite destinations, his passion bubbles over to form a list of almost twenty cities from all stretches of the world, including Sydney, Stockholm and Seattle.

For Malloy, though, there is still no place quite like his home at Notre Dame. “I live in the lap of luxury [in Sorin] … There is a great rapport, and people love living there,” he says. And when asked if he has any advice for his fellow Otters and for all Notre Dame students, Malloy offers up four succinct phrases:

“Study hard, be generous, be a leader, pray.”

Father John Jenkins (President 2005 - Present)

On April 30, 2004, the Notre Dame Board of Trustees elected Father John Jenkins as the university’s 17th president. Since his inauguration on July 1, 2005, Jenkins has worked as Notre Dame’s central leader and representative to the world. From his office in 400 Main Building, Jenkins considers the thoughts and feelings that ran through his mind on the day of his election.

“I think I had a sense of responsibility,” he says. “I think Notre Dame is a special place in so many ways, in people’s minds, in this nation, in the Church and many, many arenas. So a responsibility to do that well and a kind of determination to be forward looking.”

Jenkins also says that he felt a religious affirmation upon taking the job. “I think I did have a sense at that time that this is what God wanted me to do, so I think I felt a sort of peace that I can only do my best at this and try and always be aware of the guidance of God in my life. And to trust in that,” Jenkins says.

Notre Dame’s current president did enter his office as a veteran administrator, having also previously taught in the philosophy department and earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees in philosophy from Notre Dame. Jenkins served as a vice president and associate provost under his predecessor Fr. Malloy, and he appreciates having had the experience of “seeing his leadership.”

“[Malloy] had great success in moving the university forward, raising funds and building a team to do that. So all of those things helped us. I inherited a university in very healthy financial shape, which was very positive,” Jenkins says.

In his day-to-day life now, Jenkins echoes Malloy’s statement that no two days are alike. “It’s true that there isn’t a single typical day, where things are routine. Things come up, different things at different times, there are things you have to do,” he says. Jenkins says that his main routine tasks include general correspondence, such as making phone calls and answering emails. He also emphasizes his steady responsibility of managing people, including the eight people that report directly to the president, as well as various groups within the administration, such as the President’s Leadership Council.

Jenkins also mentions his role as the university’s chief communicator and in informing benefactors about various goings-on at Notre Dame. “[Donors are] a significant aspect, and I would say a lot of it is that we couldn’t run Notre Dame if a lot of people weren’t very generous in supporting it. Whenever they’re generous they want to know what’s going on, so a good amount of my time is spent in that area,” he says.

Despite the fact that each day is different, Jenkins says that he tries to structure his time in consistent ways. “I usually do some exercise in the mornings. I like to do that. It relaxes me,” he says. Jenkins then comes to his office around 9:00 a.m. to meet with his chief of staff, Ann Firth, and receive a number of briefings.

After discussing various issues on the table, Jenkins likes to retreat to his office to contemplate some larger issues in quiet isolation. “I do think that one of the things that’s important to do is to reserve time to think about complex issues, because the pressure is always to act, act, act,” he says. “I think if I do that, I know I’m not as effective if I’m not pondering the important questions. I do try to reserve time to do that and think.”

In the late morning and afternoon, the president’s day is booked full with meetings and often lunches, dinners and talks. On the other end of the spectrum, the demands of the office also draw Jenkins overseas to many diverse destinations. Recently, Fr. Jenkins headed a Notre Dame delegation to Rome, leading a group that included Malloy and the Board of Trustees. Pope Francis offered each member of the delegation an individual hello during the papal audience, and Jenkins was impressed by the pope’s down-to-earth candor.

“He communicates so well with a smile and he has a warm and very welcoming presence … He’s just an easy person to be with,” Jenkins says.

Jenkins uses the same phrase to describe United States President Barack Obama, whom the Notre Dame community welcomed to campus in 2009 for commencement. “[Obama] is a very easy guy to be with. Unpretentious, easy to talk to, doesn’t make a big deal out of himself,” he says.

Despite Obama’s easy going temperament, though, Jenkins recalls a tension that filled the air surrounding the historic visit. Calling the day the most memorable of his Notre Dame presidency so far, Jenkins says, “It was an intense time, let’s say that. The eyes of the world were on us.”

Notre Dame’s tendency to attract global attention adds a level of prestige, but also an added challenge to his role as university president. “It’s a big deal to be president of Notre Dame,” Jenkins says. “I really think that people expect more of Notre Dame and its graduates. They expect them to be people of character, to bring something more to the table than just being smart. And I think they expect that of the institution. I see that again and again in my interactions with people,” he says.

In trying to fulfill these expectations, Jenkins says that one of the largest challenges he faces is ultimately determining the direction of the university. “On the big issues, I have to make decisions,” he says. “I think because Notre Dame has a distinctive mission in higher education, that probably takes up more of my time … to puzzle out how all those pieces fit together and where we’re going to head in the next ten years.”

Jenkins does make sure to emphasize his priority in maintaining a strong relationship with the student body, even in the midst of contemplating the larger issues that face Notre Dame. “I want [the students] to know that I’m proud of our graduates. I think they have a sense that they represent the university in a way, and that means something. It’s not just being a smart person, but you stand for something and you have a purpose in life,” Jenkins says.

And even as students strive to live up to this high praise, Jenkins encourages them simply to “relax.” Offering advice to students, Jenkins says, “There’s a lot of pressure on people, and I think that Notre Dame students … feel some pressure about getting ahead or getting a job.”

“But I would give them the same advice that I got when I took this job: Trust that God has a plan for your life, follow that with enthusiasm and you’ll wind up in the right place,” he says.

As far as where Notre Dame winds up down the line, Jenkins says that the university will continue to “do great things” if it remains grounded in the talent and drive of its students, faculty members and administrators. He also says that Notre Dame has a chance to progress even farther on the world stage.

“I think Notre Dame has a role to play in being an extremely prominent university, a religious university, a university of faith, a university committed to service to the world, not simply to the usual things,” Jenkins says.

“There’s a kind of boldness about Notre Dame that [university founder] Father Sorin had, a bold vision. So, to move ahead in that regard is what I hope we can do.”

Photos by Daniel Domingo, Santiago Rolon, and courtesy of WikiMedia Commons