"

"

The 1960s were a tumultuous time in America, especially during the Vietnam War. At Notre Dame, Fr. Hesburgh often clashed with students who felt that he was not taking a strong enough anti-war stance. He respected their right to free speech and peaceful protest, but he was not against intervening when they threatened to burn down the ROTC building and staged a lie-in during CIA and Dow Chemical interviews on campus. He even had to face Sorin Hall (now Sorin College) seceding temporarily from the university.

ROTC was a major point of contention for many students on campus, because they felt it supported the Vietnam War and the draft. In response, Hesburgh gave a speech telling the students, “that like them I was against the war in Vietnam, but unlike them I was in favor of the ROTC on college campuses. Why? Because as long as nations needed armies, I believed the United States should have the best army possible.”

He said, “I always believed that most of the students knew I agreed with them on many issues and that I had a great deal of sympathy for them. I’m not sure how well I communicated that, but it was there.”

Some students, like Mike Neumeister, class of 1969, were aware of Hesburgh’s well-meaning intentions. He says, “As a college administrator, he knew in four years most students move out and move on to another life, so the characters were always changing. But as our local parent and president of the most renowned Catholic university in the US, he set a moral tone of leadership that we all learned and thereafter carried into our daily lives.”

Not all students felt the same. Mike Powers, class of 1969, says, “We were disappointed that Fr. Hesburgh didn’t take an anti-war stance. I think that he believed that the war was wrong. But he didn’t openly espouse that view, as far as I know. I suppose he may have thought it inappropriate for the university’s president to take such a position. I think he was wrong about that. It would have been a very strong statement coming from him.”

At times there was a disconnect between student perceptions and administrative action. But after Hesburgh’s speech, students asked for copies, which were signed by 23,000 people. Hesburgh mailed them to the White House as promised.

“The discussion and the internal conflict grew exponentially similar to the war at that time,” Neumeister says. “Not in a negative way, but as one would expect in an environment of higher learning with brilliant minds challenging the status quo.

Naturally there were always those who took the lead to challenge authority. What more could we, as Notre Dame do, could Hesburgh do as a recognizable world leader, to affect change?”

Student action during this time period was often very democratic. An all-night meeting was held to decide whether or not to burn down the ROTC building. Everyone who wanted to talk could and after being put to a vote, it was decided that the building would be left alone.

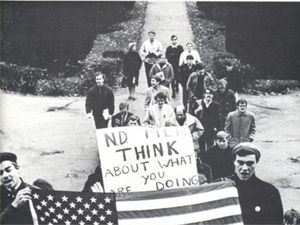

The war pervaded campus on a daily basis, whether there were demonstrations, marches, fliers, students on soapboxes or mini classes being carried out.

Neumeister recalls the growing attention the war received on campus. “I recall my first interface with campus free speech, sometime in the Fall of 1965 while studying in the library on a Sunday evening, in the basement where we took a break at then the vending machines, when a grad student pulled out the proverbial soap box to draw attention to himself as he denounced what was happening in Southeast Asia and, of course, try to elicit discussion, debate and support of his position. Until that moment I never paid real close attention to the war. For me this was opening day to what a college campus was expected to encourage…an open, stimulated, intellectual discussion of alternative points of view,” he says.

Powers also felt the war permeated campus. He says, “In my group of political activists the war was on our mind every day. There were things going on all the time e.g. ‘Guerilla Theater’ where we’d stage a little spontaneous ‘play.’ There were demonstrations when the ROTC had an event. There was a lot going on. When student elections came around, the hawk/dove position of the candidate was very important.”

The war stance of student leaders was so important that Powers estimates that 80-90 percent of students voted in the elections.Hesburgh sought input from the various campus factions whenever possible and he recognized and protected their first amendment rights.

Hesburgh said, “I was in favor of the right to protest, but not when the protest interfered with the right of students being able to attend their classes or administrators being unable to get into their offices.”

One of the biggest protests on campus was when the CIA and Dow Chemical (the company that made napalm) came to recruit and interview students on campus in November of 1968. The first two days students carried signs and marched. On the third day students staged a lie-in in front of the office where the interviews were being held in Main Building.

“One group wanted to block the doors and prevent interviewing,” Powers says. “The other group wanted to cover the floor with students lying down and force those who wanted to be interviewed to walk over the bodies. The idea was that if you wanted to work for one of these organizations, you need to learn to walk on people.”

Hesburgh would not permit the lie-in, despite the student leader of the protests requesting permission. To break up the lie-in, Hesburgh sent the dean of students, Jim Riehle.

Powers remembers the event well. “Fr. Riehle kept coming out and telling everyone to disband, but no one would leave. At one point Tom Henehan (one of the demonstrators) asked that everyone put their IDs in a paper bag in readiness for what he expected to happen. The next time Fr. Riehle came out, he said, ‘If you don’t leave, we’re going to collect your IDs. Tom said, ‘No problem Father. I already collected them for you. Here they are,’” Powers says.

“They didn’t know what to do. We were serious. You can also see the types of risks people would take for the cause. We didn’t know what was going to happen. Luckily they didn’t expel anyone. The next year they instituted the 15 minute rule,” Powers says.

As Hesburgh recounted the episode in his autobiography, God, Country, Notre Dame, Riehle gave the students an initial warning, saying he would return in 15 minutes. Approximately 20 minutes later, he returned to find them still there. He picked up their IDs, told them they were suspended for the rest of the year and threatened expulsion if anyone was still there five minutes later. No students remained.

To deal with any future situations, Hesburgh implemented the 15-minute rule, which said, “Anyone or any group that substitutes force for rational persuasion, be it violent or nonviolent, will be given 15 minutes of meditation to cease and desist…If they do not within that time period cease and desist, they will be asked for their identity cards. Those who produce these will be suspended from this community as not understanding what this community is.”

According to Neumeister, most students were not strongly opposed to the rule. “It sent shock waves through the campus,” Neumeister says. “Naturally it impacted on what the students deemed their right to free speech while Fr. Ted received national attention ‘at our expense.’ But Fr. Hesburgh recognized when the limits were being exceeded and a line had to be drawn. It was a very simple and practical solution to a very emotional complicated situation. At the end of the day most students had no problem with this new rule as the majority did not like being impacted by the more militant minority.”

All of the students returned the next semester and went on to graduate.

In a surprising, but important joint action, 40-50 student activists met with Father late in March 1969 to ask for courses, programs and library materials related to nonviolence. Hesburgh loved the idea and promised the students that if they would work on the faculty, he would find the money. As providence would have it, Alex Lewis, vice president of Gulf Oil who was in charge of their charitable foundation, called the next morning offering the university $100,000 to do with as it pleased.

After obtaining Gulf Oil’s permission to use the money for such studies, he received a call from an Observer reporter looking for the details of Hesburgh’s agreement with the student activists. The student was skeptical that such money would ever materialize, but Hesburgh gleefully told him he had the check in hand.

Hesburgh said, “I love that story because it’s such a great example of the way the providence of God works. There’s a famous line that I like to quote when I try to persuade cynics to have faith about the future: ‘The one thing we really know about tomorrow is that the providence of God will be up before dawn.’”

The program on nonviolence has expanded greatly since that 1960s and now exists as Peace Studies.

If little else is remembered about Notre Dame during the Vietnam War, it is important to emphasize that Hesburgh was in a difficult position but always strove to protect the students’ rights and promote their learning. Sometimes that meant forgiving student rebellion and allowing them some concessions. Sorin still bears a sign reading Sorin College over their front door. But other times, that meant convincing national leaders in Washington not to intervene in campus protests.

In a letter to Richard Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, Hesburgh wrote, “The vast majority of university and college students today are a very promising and highly attractive group of persons: They are more informed, more widely read, better educated, more idealistic, and more deeply sensitive to crucial more issues in our times, more likely to dedicate themselves to good rather than selfish goals than any past generation of students I have known.”

It was this environment of love, compassion, learning and intellectual curiosity that Hesburgh fostered that remains an important part of his legacy from the Vietnam era. As Neumeister says, “I was not a college protestor in the classic way it is pictured, but I observed and learned how to protest and effect change in a more thoughtful, practical way… [Hesburgh] set a bar that really has never been reached since that time. He was able to manage an uncomfortable situation, resolve the issue of the moment, and bring positive change for the community for which he served and he was an example for others.”